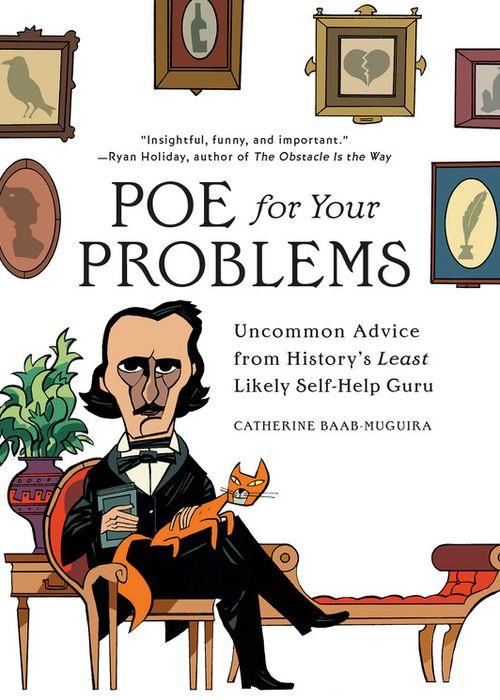

This is a historic day in TBR Stack: my first-ever self-help book! As I operate from a deep well of resentment and self-loathing, I never read self-help books—I honestly don’t know who I’d be if I got better. But when our resident Wheel of Time reader recommended Poe for Your Problems it seemed like I might have found the self-help book for me, and I was right. Baab-Muguira draws life lessons from Edgar Allan Poe’s tortured miserable life to offer advice to artists, writers, depressives, megalomaniacs, the terminally online

And again, I don’t read in this genre, but this book is hilarious and honestly helpful.

“I am not ambitious—unless negatively,” Poe once told a friend. “I, now and then feel stirred up to excel a fool, merely because I hate to let a fool imagine he may excel me.”

In case you’re not sure how this works, this is one of the many Poe quotes Baab-Muguira uses to illuminate her thesis. Yes, by all reasonable standards, Poe’s life sucked. But the important thing is that Poe also became an original thinker, a great writer, and a notorious person, and we’re still reading him nearly 200 years later, while most of his contemporaries and critics have been lost to time. And it’s by studying his “flaws” and idiosyncrasies, and embracing them, that we might unlock our greatest potential. Or, as Baab-Muguira, our “Poe-tential”. And yes, there she also refers to this as a “Poe-gram”, and includes quizzes and charts in each chapter to help you track your progress. My personal favorite of these is the handy timeline titled “How Long Did Poe Work There?” which illuminates the fact that Poe never managed to hit his 2-year anniversary at any of his magazine gigs, so if you’re a leaf on the wind of the gig economy, you are not alone.

Buy the Book

Poe for Your Problems

This book belongs to one of my favorite subgenres: the satire that actually Does the Thing. If you want to read this book purely as a parody of typical self-help fare, you can totally do that and have a great time. But you might notice as you read that you’re actually ingesting some good advice from an unlikely source. Are you fueled by pettiness and the desire to show a detractor they were wrong? So was Poe! But rather than beating yourself up, look to Baab-Muguira’s words that “Energy has to come from somewhere, and resentment is a renewable resource. The more you stew, the more you dwell on it, the more you have!” Are you anxiety-riddled, neurotic, a worrier? So was Poe! So were a lot of successful writers, including the author of an early self-help book called Be Glad You’re Neurotic! Baab-Muguira points out that most people are encouraged to fight their anxiety, but she argues that it was Poe’s anxious nature that drove him to contemplate himself and lose himself in thought, which in turn led to his singular writing.

She breaks Poe’s life down into five sections:

- His operatically tragic childhood (sample chapter: “Chip on Your Shoulder? Good!”)

- His youthful career (sample chapter: “How to Conduct Yourself in a Feud”)

- Sex and Death (sample chapter: “How to Lose at Love like a Real Romantic”)

- His mature, extremely troll-y career (sample chapter: “Thriving Through Self-Sabotage”)

- And finally, “The Poe-pose Driving Life” which gives an overview of how his alcoholism and melancholy sometimes became strengths

At each point, she takes incidents in Poe’s life that could be seen as catastrophes and teases out the ways they made him a better writer… or at least a more notorious one. As Baab-Muguira outlines, he was adopted into a wealthy Southern family after his father’s abandonment and mother’s death, and spent his earliest years ricocheting between feeling like an outcast and an orphan, and expecting to spend his life as a genteel full-time poet. But then his adoptive father turned on him, he responded by gambling and drinking, and by the time he was college age his sympathetic adoptive mother was also dead, and he’d been chucked out of the family and disinherited. So began a cycle of writing furiously, pissing people off, borrowing money, drinking, repenting, and starting all over again. Because that’s the key with Poe—no matter how dire his life became, he kept writing. He managed to become one of the first writers in the U.S. to make a (shitty) living entirely from his writing and freelance editorial work. And it was his melancholy and weirdness that helped create work that still resonates with people now. So, Baab-Muguira argues, maybe we should look to exactly the qualities that made Poe such an outcast in his own time, as he was a broke would-be writer who had to make his way via cobbled together gigs, during a time that was both one of the worst economic periods in U.S. history, and an explosive information age.

Hmmm.

Creative work, though more than a mere coping mechanism, is one hell of a coping mechanism. It’s a way of imposing order on a chaotic universe and of organizing your own disparate, often nonsensical experience. According to twentieth- and twenty-first-century science, sustained dedication to craft results in intense psychological benefits, which means your creative work can bring you more relief, more release that ever thought possible.

Baab-Muguira doesn’t just stop at making jokes about Millennial lives being dumpster fires, however. She goes beyond satire or easy jokes to link Poe’s life and work to larger psychological concepts. For instance, Baab-Muguira explains Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s idea of the “flow state”: “Time passes, unnoticed. The whole muttering, clattering world drops away. For however long you’re in flow, you’re weightless. You’re no longer struggling but experiencing a temporary reprieve from your suffering, a slipping out of the grip of depression, anxiety, unhappy tension.”

She then gives us Poe’s explicit description of that state: “Whenever, on account of its vagueness, I am dissatisfied with a conception f the brain, I resort forthwith to the pen, for the purpose of obtaining, through its aid, the necessary form, consequence and precision,” Poe said, explicitly describing his artistic process in terms of the relief it provided. Elsewhere he described “that cool exercise of consciousness,” “that deep tranquility of self-inspection” through which we glimpse “the most sublime of truths.”

But at the same time, one of the points of her book is to provide a corrective to the “Live Laugh Love” philosophy, so she never sugarcoats Poe’s actual life instead mining his “darker” attributes for inspiration in the same way. His tendency to self-sabotage? With a little massaging, you could see his public wars of insults with other writers as press—bad press, sure, but it certainly got his name out there. After his wife’s death, rather than having a quiet nervous breakdown, Poe composed a long pseudo-scientific work called Eureka in which he tried to explain the birth of the universe. Was this a naked attempt to find meaning in personal tragedy? Yes! But Eureka also has some fascinating ideas in it! If you’re in great pain, it might be worth it to try to express that through art of some kind—though you probably don’t want to do what Poe did next, which was storm into a publisher’s office and insist your grief-driven prose poem will be a bestseller. It…was not. And about all that drinking. Baab-Muguira talks about his tendency to binge-drinking, and quotes one of the (presumably numerous) hungover apology letters that he sent to friends:

Please Forgive me my petulance & don’t believe I think all I said…Please express my regret to Mr. Fuller for making such a fool of myself in his house, and say to him (if you think it necessary) that I should not have got half so drunk on his excellent Port wine but for the rummy coffee with which I was forced to wash it down.

While she responsibly notes that if a reader needs help they should seek it (emphatic co-sign!) she also points out that life sucked in Poe’s time, and it sucks now, and that sometimes altering your consciousness is actually the best way to cope. By the standards of the 1840s, Poe didn’t actually drink that much—he just took it too far when he did drink.

Getting too drunk every once in a while might have cost him dearly, but it brought him something, too, he explained. It, too, was about the struggle to glimpse a better, fairer, more beautiful world. “There are few men of that peculiar sensibility which is at the root of genius, who, in early youth, have not expended much of their mental energy in living too fast; and, in later years, comes the unconquerable desire to goad the imagination up to that point which it would have attained in an ordinary, normal, or well-regulated life,” Poe wrote in 1845. “The earnest longing for artificial excitement, which, unhappily, has characterized too many eminent men, may thus be regarded as a psychal want, or necessity,—an effort to regain the lost,—a struggle of the soul to assume the position which, under other circumstances, would have been its due.”

She concludes this section by pointing out that Byron looked at drinking as a necessary escape from the tyranny of reason, Mark Twain thought people should indulge in a few vices just so they’d have something to recover from, and Rasputin took that further by pointing out that if you don’t sin, you render God’s forgiveness moot. (I knew I liked the cut of Rasputin’s jib.) She closes with a recipe for “Peach and Honey”, a drink that was popular at UVA while Poe was there—how many self-help books include cocktail recipes??? Not enough I say.

But do be super clear: Baab-Muguira also hammers home the idea that Poe was not some figure out of Romantic myth who staggered shit-faced through life, only to reel home and dash off an effortless masterpiece. Part of the point of the Poe-gram is to embrace your weirdness. Forgive yourself for your trashbag tendencies and don’t worry so much about the fact that you worry. But the other part is that have to put in your work—whatever that work is. Between the binges, Poe worked constantly, from book reviews (the work that brought him the most notoriety during his life) to editing, to trying to drum up funding for journals, to the short stories all of us have probable read. And he did all of that as his day job, when what he really wanted to be doing was writing poetry.

Even the geniuses struggle. Even the geniuses end up continually revising. Poe, whatever else he said about his process, spent most of his hours with his ass glued to the seat of some dumb, hard chair. He wrote and rewrote, struggling to find time on top of day jobs when he was lucky enough to have those day jobs. Now think of how misunderstood Poe was during his lifetime, despite those efforts. He’s come in for enormous reevaluation since, and his reputation has grown, but while he was alive, the struggle and sorrow were constant, virtually never-ending. On top of the struggle to compose, there was the struggle to live, and one was not necessarily separable from the other. The same will be true for you.

Poe for Your Problems is available now from Running Press

Leah Schnelbach knows that as soon as this TBR Stack is defeated, another shall rise in its place! Come join them on the bust of Pallas above the chamber door that is Twitter!